The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held on December 18, 2020, that the Oh, the Places You’ll Go! comic book infringed the rights of the owner of the Oh, the Places You’ll Go! Dr Seuss book as it is not fair use.

The case is Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. v. Comic Mix LLC.

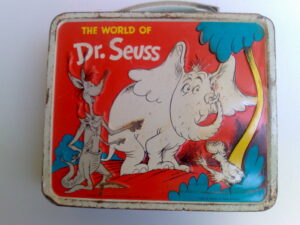

Appellant is Dr. Seuss Enterprises (DSE) which holds the copyright to the works of Theodor S. Geisel, aka “Dr. Seuss,” including his final book, Oh, the Places You’ll Go! (Go!) and runs a product licensing and merchandising program. The Ninth Circuit noted that “Dr. Seuss” was the top licensed book brand in 2017, and a popular choice as graduation present.

Appellee Comic Mix developed and published the Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go! book (Boldly) which is a mash-up of the Dr. Seuss book and Star Trek, using elements from each of works. “Mash-up” refers to a work created from combining elements of others works but is not a legal term. If a mash-up uses elements protected by copyright, it may not be infringing if it is fair use. Comix Mix did not seek to obtain a license from DSE, nor did it obtain authorization to use elements of Go!.

DSE considered the mash-up to be infringing and sent several letters to Defendants. It also sent a DMCA takedown notice to Kickstarter, which then took down the fundraising page and blocked the pledged funds. DSE then filed a copyright and trademark infringement suit. Comic Mix had sought to fund the publication of the book by a Kickstart crowdfunding campaign.

Comic Mix moved to dismiss the trademark infringement claims arguing that use of the trademarks in the title, artistic style or fonts of the mash-up book is protected by the First Amendment under the Rogers v. Grimaldi test, which requires judges to examine if (1) the mark has artistic relevance and (2) if so, if use of the work is explicitly misleading. The District Court dismissed Plaintiff’s trademark claim, finding that that use was nominative fair use.

Comix Mix also argued that the mash-up was a parody and thus fair use. While a parody is fair use, fair use can be found by the courts even if the derivative work is not a parody. As defined by the Supreme Court in its 1994 Campbell case, a parody uses elements of the original work to comment, at least in part, on the author of the work. Fair use, in contrast, is determined by examining four fair use factors. The District Court did not find the mash-up to be a parody, but granted summary judgment, because the mash-up was fair use.

DSE appealed and a panel of Ninth Circuit held an hearing on April 27, 2020. DSE’s counsel argued that Boldly! is a “market substitute” for Go! and that it “would compete head-to-head in the graduation gift market.” Comic Mix’s counsel argued it was a parody. .

On December 18, 2020, the panel reversed the US District Court’s grant of summary judgment, finding that the use was not fair use.

The Four fair Use Factors

The first fair use factor, the purpose and character of the use, weighed against fair use. The use is commercial, and the mash-up is not a parody, as it does not critique or ridicule Dr. Seuss’s works. The panel did not find use of the original work to be otherwise transformative either, but that Boldly! “merely repackaged Go!.” There was no new purpose or character, according to the Ninth Circuit but Boldly! merely recontextualized the original expression. It “[did] not alter Go! with new expression, meaning or message” either, noting that “the world of Go! remains intact, ” and that the derivative work “was merely repackaged into a new format, ” noting further that the “Seussian world… is otherwise unchanged.”

The second fair use factor, the nature of the work, also weighed against fair use, as Go! is a creative and expressive work.

The third fair use factor, the amount and substantiality of the use, weighed “decisively” against fair use, as both quantitative and qualitative use were substantial. The Ninth Circuit found the copying to be “considerable,” around 60% of the Dr. Seuss’s book, including illustrations, and “took the heart of Dr. Seuss’s works, ”giving as example the use of the “highly imaginative and intricately drawn machine that can take the star-shaped status-symbol on and off the bellies of the Sneetches,” from the Sneetches book.

The fourth and final factor, the effect of the use on the potential market, also weighted against fair use. It is the proponent of the affirmative defense of fair use who has the burden of proof, and the Court did not find that Comic Mix had not proven there was no potential market harm. Comic Mix tried unsuccessfully to argue that fair use is not an affirmative defense and that it was thus DSE which had to prove potential market harm. Counsel for DSE argued during the April 2020 hearing that the District Court had incorrectly place the burden of proof of the fourth factor on DSE, a decision he found to be “inconsistent” with Campbell.

The Ninth Circuit noted that Comic Mix had “intentionally targeted and aimed to capitalize on the same graduation market as Go!” and that it had planned to release Bold! “in time for school graduations,” and that the unauthorized derivative work curtailed Go! ‘s potential derivative market, noting further that DSE “[had] already vetted and authorized multiple derivatives of Go! ”. DSE’s counsel reminded the panel during the April 2020 debate that the Supreme Court had emphasized in Campbell that licensing of derivatives is an important incentive to creation.[

Comic Mix’s counsel argued, curiously, that DSE did not have the right to control the “fair use market for transformative work,” but acknowledged that DSE was entitled to make transformative works. Indeed, this right is provided to DSE by Section 106 (2) of the Copyright Act. The Ninth Circuit noted that DSE “certainly has the right to “the artistic decision not to saturate those markets with variations of their original,” citing Castle Rock Ent., a case where the Second Circuit Court of Appeals stated that even though the owner of the copyright of the Seinfeld television series “[had] evidenced little if any interest in exploiting this market for derivative works based on Seinfeld, such as by creating and publishing Seinfeld trivia books… the copyright law must respect that creative and economic choice.”

Image is courtesy of Flickr user Sarah B Brooks under a CC BY 2.0 license.