California enacted on September 23rd a “right to be forgotten” law. SB 568 was passed to give “Privacy Rights for California Minors in the Digital World.” The law, which is now part of the California Online Privacy Protection Act, will take effect on January 1, 2015.

California enacted on September 23rd a “right to be forgotten” law. SB 568 was passed to give “Privacy Rights for California Minors in the Digital World.” The law, which is now part of the California Online Privacy Protection Act, will take effect on January 1, 2015.

Under §22581(a) of the law, operators of web sites or apps “directed to minors” which have “actual knowledge” that a minor is using the site/app, must allow minors who are registered users of their service “to remove or, if the operator prefers, to request and obtain removal of, content or information posted on the operator’s Internet Web site, online service, online application, or mobile application by the user.”

Operators must provide notice to minors that such removal service is available to them and also provide them “clear instructions” on how to remove or to request removal of content or information. The notice must also inform minors that the removal “does not ensure complete or comprehensive removal of the content or information posted.”

Exceptions to the Right to Be Forgotten

There are five exceptions to this obligation to erase information:

1. A federal or a state law requires maintaining the content or information

2. The content or information was stored on or posted by a third party, including any content or information posted by the minor that was stored, republished, or reposted by the third party

3. The operator anonymizes the content or information posted by the minor in such way that the minor cannot be individually identified

4. The minor does not follow the instructions provided by the operator on how to erase or require deletion of the information or content

5. The minor has received compensation or other consideration for providing the content

Is Content Really Deleted?

Many sites already offer a delete button. Minors (and majors) can delete tweets and Facebook posts and it is easy to delete a blog post or even an entire blog in a few seconds. However, one can never be sure that the information has been deleted from servers.

Also, as data is frequently republished by third parties, deleting all the subsequent reposting of that information is impossible, hence the necessity of the third-party republication exception of the California law.

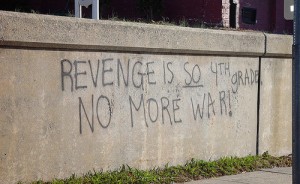

The Particular Issue of Cyber Revenge

This is good news from a free speech point of view, but it is not good news for victims of cyber bullying and cyber revenge. The New York Times published a sobering article on revenge porn last week, describing the plight of a young girl whose former boyfriend had posted online intimate pictures of her out of spite.

The article mentions that owners and operators of porn revenge sites are in most cases protected by federal law.

Indeed, under Section 230 of the Communication Decency Act (CDA), 47 U.S.C. §230, “[n]o provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” The law provides a safe harbor to Internet service providers from speech posted by a third party.

Section 230 of the CDA has, however, no effect on criminal law or intellectual property law. That means that if the image of a naked minor is posted on a porn revenge site, and the State where the posting took place considers that such posting constitutes child pornography, the porn revenge site will not be able to use Section 230 of the CDA as a defense.

Also, if a posting falsely implies that the person featured would freely engage in sexual activities if asked and/or paid for this service, it would defamatory, and the victim could sue the site. However, most posts show a picture and identify the subject of the photograph, without further comment.

Copyright law could also be used to have a photograph taken down, but only if the subject of the photograph owns its copyright. That would be the case if racy ‘selfie’ is emailed to, say, a boyfriend, who later posted it on a site out of spite. In that case, the subject of the photograph could use another federal law, the Digital Millenium Copyright Act, to require the site to takedown the photograph. In order to be protected by copyright however, the ‘selfie’ would have to be original, but the threshold for protection is low.

It could also be argued that porn revenge is a breach of the federal stalking law, 18 U.S.C. § 2261A, passed as part of the Violence Against Women Act. This act, 18 U.S.C. § 2261A(2) specifically incriminates stalking using a computer.

Another new California law, SB 255, was enrolled on September 19 and specifically addresses the issue of cyber revenge. It is now a crime in California to publicize the picture of someone partially or completely naked, even if the person has given his consent to have this picture taken, defined as follows:

“Any person who photographs or records by any means the image of the intimate body part or parts of another identifiable person, under circumstances where the parties agree or understand that the image shall remain private, and the person subsequently distributes the image taken, with the intent to cause serious emotional distress, and the depicted person suffers serious emotional distress.”

The author of the bill, California Senator Anthony Cannella, argued that such law was necessary to protect victims of cyber-bullying, especially since some victims have committed suicide as a result of being bullied online.

The ACLU opposed the bill, arguing that “[t]he posting of otherwise lawful speech or images even if offensive or emotionally distressing is constitutionally protected. The speech must constitute a true threat or violate another otherwise lawful criminal law, such as stalking or harassment statute, in order to be made illegal. The provisions of this bill do not meet that standard.”

The ACLU cited in its argument the United States v. Cassidy case, where the defendant had argued that 18 U.S.C. § 2261A(2)(A) violated the First Amendment because it was overbroad. The District Court of Maryland found in favor of defendant, reasoning that the government’s indictment was directed at protected speech, described by the court as “anonymous, uncomfortable Internet speech addressing religious matters” (at 583).

The court also noted that this speech did not fall into any of the categories of speech outside First Amendment protection, that is, obscenity, fraud, defamation, true threats, incitement, or speech integral to criminal conduct.

The questions of whether porn revenge postings are protected by the First Amendment remains an open question, likely to be answered at one point by a court of law.

Image is Graffiti courtesy of Flickr user Cliff Beckwith pursuant to a CC BY 2.0 license.