The Third Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled on 10 November 2016 that it is legal under EU law for a library to lend an electronic copy of a book. However, only one copy of the e-book can be borrowed at the time, the first sale of the e-book must have been exhausted in the EU, and the e-book must have been obtained from a lawful source. The case is Vereniging Openbare Bibliotheken v. Stichting Leenrecht, C-174-15.

Legal framework

Article 2 of Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (the InfoSoc Directive) provides authors exclusive rights in their works, including, under its Article 3, the exclusive right to communicate their works to the public by wire or wireless means. Its Article 4 provides that these exclusive rights are exhausted by the first sale or by other transfers of ownership of the work in the EU.

Article 6(1) of Directive 2006/115/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on the rental right and lending right and on certain rights related to copyright in the field of intellectual property, the Rental and Lending Rights Directive (RLR Directive), gives Member States the right to derogate from the exclusive public lending right provided to authors by Article 1 of the RLR Directive, provided that authors are compensated for such lending.

Article 15c(1) of the Dutch law on copyright, the Auteurswet, authorizes lending of a copy of a literary, scientific, or artistic work, provided that the rightsholder consented to the lending and is compensated for it. The Minister of Justice of the Netherlands set up a foundation to that effect, the Stichting Onderhandelingen Leenvergoedingen (StOL), which collects lending rights payments as a lump sum from lending libraries and then distributes those payments to rightsholders through collective management organizations.

The Dutch government took the view that e-books are not within the scope of the public lending exception of the Auteurswet and drafted a new law on that premise. The Vereniging Openbare Bibliotheken (VOB), which represents the interests of all the public libraries in the Netherlands, challenged this draft legislation and asked the District Court of The Hague to declare that Auteurswet covers lending of e-books.

The Court stayed the proceedings and requested a preliminary ruling from the CJEU on the question of whether Articles 1(1), 2(1)(b) and 6(1) of the Renting and Lending Rights Directive authorize e-lending, provided that only one library user can borrow the e-book at a time by downloading a digital copy of a book which has been placed on the server of a public library.

If this is indeed authorized by the Directive, the District Court asked the CJUE whether article 6 of the Directive requires that the copy of the e-book which is lent has been brought into circulation by an initial sale or other transfer of ownership within the European Union by the rightsholder, or with her consent within the meaning of Article 4(2) of the InfoSoc Directive.

The District Court also asked whether Article 6 of the RLR Directive requires that the e-book which is lent was obtained from a lawful source.

Finally, the District asked the CJEU to clarify whether e-lending is also authorized (if the copy of the e-book which has been brought into circulation by an initial sale or other transfer of ownership within the European Union by the right holder or with her consent) when the initial sale or transfer was made remotely by downloading.

First: Is e-lending legal under the renting and lending rights directive?

The CJEU noted that Article 1(1) of the RLR Directive does not specify whether it also covers copies which are not fixed in a physical medium, such as digital copies (§ 28). The CJEU interpreted “copies” in the light of equivalent concepts of the WIPO Copyright Treaty of 20 December 1996, which was approved by the European Community, now the European Union. Its Article 7 gives authors the exclusive right to authorize “rentals” of computer programs. However, the Agreed Statements concerning the WIPO Copyright Treaty, which is annexed to the WIPO Treaty, explains that Article 7’s right of rental “refer[s] exclusively to fixed copies that can be put into circulation as tangible objects,” thus excluding digital copies from the scope of Article 7.

The Court noted, however, that “rental” and “lending” are separately defined by the RLR Directive. Article 2(1) (a) defines “rental” as “making available for use, for a limited period of time and for direct or indirect economic or commercial advantage,” while Article 2(1) (b) defines “lending” as “making available for use, for a limited period of time and not for direct or indirect economic or commercial advantage, when it is made through establishments which are accessible to the public.” The Court examined preparatory documents preceding the adoption of Directive 92/100, which the RLD Directive codified and reproduced in substantially identical terms, and noted that there was “no decisive ground allowing for the exclusion, in all cases, of the lending of digital copies and intangible objects from the scope of the RLR Directive.” The Court also noted that Recital 4 of the RLR Directive states that copyright must adapt to new economic developments and that e-lending “indisputably forms part of those new forms of exploitation and, accordingly, makes necessary an adaptation of copyright to new economic developments” (§ 45).

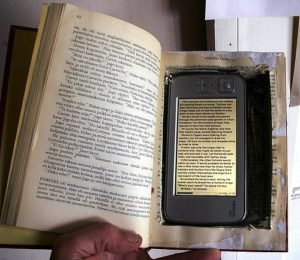

The CJEU noted that borrowing an e-book as described by the District Court in its preliminary question “has essentially similar characteristics to the lending of printed works,” considering that only one e-book can be borrowed at the time (§ 53). The CJEU therefore concluded that that “lending” within the meaning of the RLR Directive includes lending of a digital copy of a book.

Second: May only e-books first sold in the EU be lent?

The InfoSoc Directive provides that the exclusive distribution rights of the author are exhausted within the EU after the first sale or other transfer of ownership in the EU of the work by the right holder or with his consent. Article 1(2) of the RLR Directive provides that the right to authorize or prohibit the rental and lending of originals and copies of copyrighted works is not exhausted by the sale or distribution of originals and copies of works protected by copyright.

The CJEU examined Article 6(1) of the RLR Directive in conjunction with its Recital 14, which states it is necessary to protect the rights of the authors with regards to public lending by providing for specific arrangements. This statement must be interpreted as establishing a minimal threshold of protection, which the Member States can exceed by setting additional conditions in order to protect the rights of the authors (at 61).

In our case, Dutch law required that an e-book made available for lending by a public library had been put into circulation by a first sale, or through another transfer of ownership, by the right holder or with his consent within the meaning of Article 4(2) of the InfoSoc Directive. The Court mentioned that Attorney General Szpunar had pointed out in his Opinion that if a lending right is acquired with the consent of the author, it may be assumed that the author’s rights are sufficiently protected, which may not be the case if the lending is made under the derogation provided by Article 6(1) (Opinion at 85). AG Szpunar concluded that therefore only e-books which had been made first available to the public by the author should be lent. The CJEU ruled that Member States may subject as condition to e-lending the fact that the first sale of the e-book has been exhausted in the EU by the right holder.

Third: May a copy of an e-book obtained from an unlawful source be lent?

Not surprisingly, the CJEU answered in the negative to this question, noting that one of the objectives of the RLR Directive, as stated by its Recital 2, is to combat piracy and that allowing illegal copies to be lent would “amount to tolerating, or even encouraging, the circulation of counterfeit or pirated works and would therefore clearly run counter to that objective” (at 68).

The Court did not answer the fourth question as it had been submitted only in the case the Court would rule that it is not necessary that the first sale of the e-books being lent had been exhausted in the EU.

This is a welcome decision since, as noted by AG Szpunar in his Opinion, it is crucial for libraries to be able to adapt to the fact that more and more people, especially younger ones, are now reading e-books instead of printed books.

Photo is courtesy of Flickr user Timo Noko under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

This article was first published on the TTLF Newsletter on Transatlantic Antitrust and IPR Developments published by the Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum