The Supreme Court agreed yesterday to review the case of Lee v. Tam. The Supreme Court will now rule on whether the disparagement provision in 15 U.S.C. 1052(a) is facially invalid under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. 1052(a), provides that no trademark shall be refused registration on account of its nature unless, inter alia, it “[c]onsists of… matter which may disparage.”

I wrote about the case on this blog three years ago and again a few months ago. Last June, I wrote about The Slants filing a petition for a writ of certiorari for the TTLF Newsletter on Transatlantic Antitrust and IPR Developments, published by the Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum. Here it is below.

Re-appropriation, disparagement, and free speech. The Slants, continued

We saw in the last issue of the TTLF newsletter that the Federal Circuit held en banc that the disparagement provision of § 2(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. 1052(a), which forbids registration of disparaging trademarks, violates the First Amendment.

The case is about the mark THE SLANTS, which Simon Tam is seeking to register in connection for live performances of his dance-rock music group. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) refused to register it, claiming it was an ethnic slur disparaging to persons of Asian ancestry. The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) affirmed, but the Federal Circuit ruled in favor of Mr. Tam and remanded the case for further proceeding.

Now the PTO has filed a petition for a writ of certiorari asking the Supreme Court to answer “[w]hether the disparagement provision in 15 U.S.C. 1052(a) is facially invalid under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”

The Federal Circuit held that §2(a) “penaliz[es] private speech merely because [the government] disapproves of the message it conveys.” The PTO argues in its petition that §2(a) does not prohibit any speech, but only “directs the PTO not to provide the benefit of federal registration to disparaging marks” (petition p. 8).

Would refusing to register THE SLANTS as a trademark merely deny Mr. Tam the benefits of federal trademark registration, or would his freedom of speech be violated?

PTO argument: Mr. Tam is merely denied the benefits of federal registration

The petition notes that federal registration does not create trademarks, but is merely “a supplement to common-law protection” and that a person who first uses a distinct mark in commerce acquires rights to this mark, citing the 1879 In re Trade-Mark Cases Supreme Court case (petition p. 3 and p. 11). The PTO further argues that “[t]he holder of a trademark may use and enforce his mark without federal registration” (petition p. 3). Mr. Tam would still have federal remedies available to him to protect his mark, even if THE SLANTS is not federally registered. For example, the Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(D), does not require the mark seeking protection to be registered (petition p. 12).

For the PTO, Section 1052(a) is not unconstitutional, as it does not prohibit speech, nor does it proscribe any conduct or restrict the use of any trademark. Instead, it merely “directs the PTO not to provide the benefits of federal registration to disparaging marks.” Since a mark can function as a mark without the benefit of federal registration, even if a mark is speech, it does not need the benefit of federal registration to be expressed, and therefore, it is not a violation of the First Amendment to refuse to register it.

The PTO further argues that the purpose of Section 1052(a) is to avoid the federal government “affirmatively promot[ing] the use of racial slurs and other disparaging terms by granting them the benefits of registration” (petition p. 10) and that “Congress legitimately determined that a federal agency should not use government funds to issue certificates in the name of the United States of America conferring statutory benefits for use of racial slurs and other disparaging terms” (p. 15-16).

However, in In re Old Glory Condom Corp.(at FN3), the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board noted that “the issuance of a trademark registration for applicant’s mark [does not amount] to the awarding of the U.S. Government’s “imprimatur” to the mark.”

PTO argument: no violation of free speech, as Mr. Tam can still use his mark to convey his message

The PTO also argues that Section 1052(a) is not an affirmative restriction on speech because the federal law does not prevent Mr. Tam “from promoting his band using any racial slur or image he wishes,” does not limit Mr. Tam’s choice of songs played, or the messages he wishes to convey (petition p. 12).

The PTO gives Sons of Confederate Veterans, Inc. as an example of a case where the Supreme Court recognized the government’s right to “take into account the content of speech in deciding whether to assist would-be private speakers.” However, this case can be distinguished from our case. The Supreme Court held in Sons of Confederate Veterans that a state can refuse to issue a specialty license plate if it carries a symbol which the general public finds offensive, in that case a confederate flag. But the owner of a car can still reap the government benefits of car registration, which is mandatory to operate a motor vehicle, even though his speech has been suppressed by the government as disparaging, while, in our case Mr. Tam cannot reap the benefits provided to the holder of a federally registered mark. The fact that he still has some benefits as the owner of a common law mark is irrelevant.

The petition also gives National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley as an example of a case where the Supreme Court upheld the government’s right to take moral issues into consideration when denying a federal benefit. In this case, a court of appeals had held that §954(d) (1) of the National Foundation of the Art and the Humanities Act violated the First Amendment. This federal law requires the Chairperson of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to make sure “that artistic excellence and artistic merit are the criteria by which applications are judged, taking into consideration general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public.” The Supreme Court found in Finley that §954(d) (1) was constitutional.

However, Finley can also be distinguished from our case. The Supreme Court noted there that respondents had not “allege[d] discrimination in any particular funding decision” and that, therefore, the Supreme Court could not assess whether a particular refusal for the NEA grant was “the product of invidious viewpoint discrimination.” In our case, we do know that the only reason the PTO refused to register THE SLANTS is because it assessed the mark to be disparaging, and so the Supreme Court could very well find this decision to be an “invidious viewpoint discrimination.” Also, while not receiving a grant from the NEA may make it more difficult for an artist to create art, it does not entirely prevent it, even a particular piece of art which would shock standards of decency.

If a mark is a racial slur, should the intent of applicant for registering the mark matter?

The TTAB affirmed the refusal to register THE SLANTS because it was disparaging to persons of Asian ancestry and because the mark was disparaging to a substantial composite of this group. The PTO noted in its petition that the TTAB had determined “that Section 1052(a) prohibits registration of respondent mark despite the fact that respondent’s stated purpose for using the mark is to “reclaim” the slur as a sign or ethnic pride” (emphasis in original text, p. 13 of the petition). The PTO seems to argue that Section 1052(a) views disparaging content neutrally, without questioning the intent behind the choice of disparaging speech as trademark.

Judge Dyk from the Federal Circuit wrote in his concurring/dissenting opinion that he would have held that Section 1052(a) is facially constitutional because “the statute is designed to preclude the use of government resources not when the government disagrees with a trademark’s message, but rather when its meaning “may be disparaging to a substantial composite of the referenced group,” citing In re Lebanese Arak Corp.” In this case, the USPTO had refused to register KHORAN as a trademark for alcoholic beverages because it was disparaging to the beliefs of Muslims.

For Judge Dyk, the purpose of Section1052(a) is “to protect underrepresented groups in our society from being bombarded with demeaning messages in commercial advertising” and Section 1052(a) “is constitutional as applied to purely commercial trademarks, but not as to core political speech, of which Mr. Tam’s mark is one example.” Judge Dyk argued further that, while the First Amendment protects speech which is offensive to some in order to preserve a robust marketplace of ideas, “this principle simply does not apply in the commercial context,” giving as example racial or sexual harassment in the workplace.

But this argument seems to make a difference between registrants: Mr. Tam could register a racial slur to make a point, but could not do so if his purpose for registering the same mark would be to insult people of Asian descent. This interpretation of Section 1052(a) is troubling, as courts would have to determine if a particular mark is indeed political speech, then decide if it is “good” political speech or “bad” political speech. This is noted by the PTO in a footnote to the petition as being viewpoint discrimination which violates the First Amendment (p. 13).

The PTO argues that if Section 1052(a) is unconstitutional, then the PTO can no longer refuse to register as a trademark “even the most vile racial epithet” (p.10). Mr. Tam does not deny that “slant” is an ethnic slur. Indeed, he choose to name his band “The Slants” because it is a slur, in order to “take on stereotypes” about Asians (petition p. 5). Therefore, the mark may be an ethnic slur, but it is not disparaging. It all depends on the eyes and ears of the beholder. This was also the idea behind the attempted registration of HEEB or DIKES ON BIKE as trademarks.

Therefore, the question of who are the members of the group of reference is important. But it should not be.

Is it possible to protect minorities and the First Amendment?

If Mr. Tam would be authorized to register his trademark, it would be a victory for freedom of speech. The Slants would be able to promote further their anti-xenophobic message, and this would benefit the nation as a whole. But what if a person or an entity wishes to trademark a racial slur in order to advocate xenophobia? Owning the trademark could then serve as a tool to censor speech opposing racism. It would not be the first time that trademarks are used to suppress speech.

One can also argue that allowing disparaging trademark to be registered could confuse consumers about the origin of the product. Some consumers would not understand that a particular term is a racial slur. Others may understand it, but not know that it was meant to be used to fight prejudice. Since the function of a trademark is also to reduce consumer search costs, federal law could create a sign informing consumers that the trademark is used in an ironic way. I propose adding in these cases an irony punctuation (¿) after®. Is it a good idea?¿

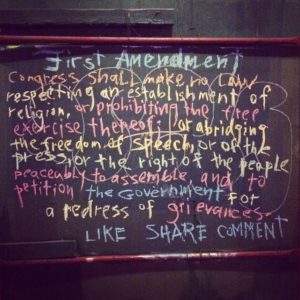

Picture is courtesy of Flickr user leesean under a CC_BY_SA-2.0 license.