Section 512(c) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) provides Online Service Providers (OSPs) four types of safe harbor against copyright infringement. In order to benefit from these safe harbors, OSPs must designate a DMCA copyright agent. Such agents are designated by the OSPs to receive notifications of claimed infringement, the “DMCA takedown notices,” which are usually sent by email.

Since December 1, 2016, OSPs must do so electronically. Even if an OSP had formally designated a DMCA agent using the paper method, it must now do so again electronically before January 1, 2018.

The Four DMCA Safe Harbors

The Four DMCA Safe Harbors

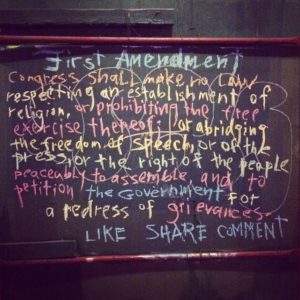

The DMCA provides a safe harbor for transitory communications. Entities merely serving as a conduit for transmitting, routing or providing connections for digital online communications that are between or among points specified by a user, of material of the user’s choosing, without modification to the content of the material as sent or received, are shielded from copyright infringement liability, Section 512(k)(1)(A).

The DMCA also provide a safe harbor to providers of online services or network access, or operators of facilities for such services, for system caching, storing information at the direction of users and providing links or other tools for locating material online, Section 512(k)(1)(B).

OSPs Must Designate a DMCA Agent

In order to benefit from these four safe harbors, OSPs must designate individuals as copyright agents and must provide this information on their website “in a location accessible to the public.” They must also provide this information to the U.S. Copyright Office, by providing the name, address, telephone number and email address of the agent.

The Copyright Office maintains a directory of these agents. The list of DMCA agents 1998-2016 is available here. This list will now be phased out. If a OSPs has a DMCA listed in this directory, it satisfies its obligation to register a DMCA agent, but only until December 31, 2017. The designation will expire after this date.

New Rule as of December 1, 2016: OSPS Must Designate their DMCA Agent Electronically

Under interim regulations in effect between November 3, 1998 and November 30, 2016, OSPs could designate agents using a paper form. This changed on December 1, 2016, when the new regulation about the new online registration system entered into force. Under the new electronic system, OSPs must now designate their agents electronically.

Therefore, an OSP wishing to retain its active designation must submit electronically a new designation using the new online registration system by December 31, 2017. The new directory is available here. Good news: the fee to register electronically is significantly lower than was the fee was to register by paper, from $106 to register by paper to $6 to register by electronically.

Image is courtesy of Flickr user Cory Doctorow under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.