The First Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) held on 10 November 2016, that the famous Rubik’s cube cannot be registered as a three-dimensional trademark because its shape performs the technical function of the goods, a three-dimensional puzzle. The case is Simba Toys GmbH & Co. KG v. EUIPO, C-30/15 P.

The validity of the Rubik’s cube trade mark was challenged by a competitor

The validity of the Rubik’s cube trade mark was challenged by a competitor

British company Seven Towns Ltd., acting on behalf of Rubik’s Brand Ltd., filed in April 1996 an application for registration of a Community trade mark at the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (OHIM), now named the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), for a three-dimensional sign, the famous Rubik’s cube. The mark was registered in April 1999 and renewed in November 2006.

A few days later, competitor Simba Toys applied to have the trade mark declared invalid under Council Regulation 40/94, which has been repealed and was replaced by Council Regulation 207/2009. The CJEU considered the case to be still governed by Council Regulation 40/94. Articles 1 to 36 are the same in both Regulations, and so the case is relevant under current EU trademark law.

Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Council Regulation 40/94 prevents registration as a trademark of a sign, such as the Rubik’s cube product, “which consists exclusively of… the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result.” The CJEU had held in the 2002 Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v. Remington Consumer Products Ltd. that a sign consisting exclusively of the shape of a product cannot be registered as a trademark if the essential functional features of the shape are attributable only to a technical result (Philips § 79 and § 80).

Simba Toys argued that the Rubik’s cube mark should be declared invalid under the grounds [absolute ground for refusal] that the mark is the shape of the goods necessary to achieve a technical result. According to Simba, the Rubik’s cube black lines are attributable to technical functions of the three-dimensional puzzle.

The OHIM dismissed Simba’s application for a declaration of invalidity and the Second Board of Appeal of OHIM affirmed the dismissal in September 2009, reasoning that the shape of the trade mark does not result from the nature of the Rubik’s cube itself. On 25 November 2014, the General Court dismissed the action for annulment as unfounded. Simba appealed to the CJEU.

What are the essential characteristics of the Rubik’s cube trade mark?

The essential characteristics of three-dimensional signs are the most important elements of the signs, Lego Juris v. OHIM, C-48/09, § 68 and 69. They must be properly identified by the competent trademark registration authority, Lego Juris v. Ohim § 68, which must then determine whether the essential characteristics all perform the technical function of the goods (General Court § 41). The General Court identified the essential characteristics of the Rubik’s cube trademark is a “cubic grid structure,” that is the cube itself and the grid structure appearing on each of its surfaces (General Court § 45). Simba did not challenge this finding on appeal at the CJEU.

Do the essential characteristics of Rubik’s cube perform the technical function of the goods?

Under Article 4 of Regulation 40/94 and Regulation 207/2009, any sign capable of being represented graphically can be a trade mark, unless, under article 7(1)(e)(ii) of both Regulations, the sign consists exclusively of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result.

Article 7(1) grounds for refusal to register a mark must be interpreted in light of the public interest underlying them. The public interest underlying Article 7(1)(e)(ii) is to prevent the use of trademark law to obtain a monopoly on technical solutions or the functional characteristics of a product (General Court § 32, citing Lego Juris v. OHIM, § 43). Advocate General Szpunar explained further in his Opinion that allowing such marks to be registered would give the registrant “an unfair competitive advantage” and thus trade mark law cannot be used “in order to perpetuate, indefinitely, exclusive rights relating to technical solutions” (AG Szpunar Opinion § 32 and § 34).

For the General Court, Article 7(1)(e)(ii) applies only if the essential characteristics of the mark perform the technical functions of the goods “and have been chosen to perform that function.” It does not apply if these characteristics are the result of that function (General Court § 53). Simba argued in front of the CJEU that the General Court erred in this interpretation of Article 7(1)(e)(ii).

Simba claimed that the black lines of the cube performed a technical function (General Court § 51). But the General Court found that an objective observer is not able to infer by looking at the graphic representation of the Rubik’s cube mark that the black lines are rotatable (General Court § 57). The General Court held that Simba’s “line of argument… [was] essentially based on knowledge of the rotating capability of the vertical and horizontal lattices of the Rubik’s cube. However, it [was] clear that that capability cannot result from the black lines in themselves or, more generally, from the grid structure which appears on each surface of the cube… but at most from [an invisible] mechanism internal to that cube” (General Court § 58). Therefore, the grid structure on each surface of the cube “d[id] not perform, or are not even suggestive of, any technical function” (General Court § 60). The General Court concluded that registering the Rubik’s cube shape did not create a monopoly on a technical solution and mechanical puzzles competitors could also incorporate movable or rotatable elements (General Court § 65).

But, for AG Szpunar, the General Court erred in its analysis as it should have taken into account the function of the Rubik’s cube, which is a three-dimensional puzzle consisting of movable elements. He noted that in both the Philips and the Lego Juris cases, the competent authorities had analyzed the shape of the goods using additional information other than the graphic representation (AG Szpunar Opinion § 86). While the competent authority does not have to concern itself with hidden characteristics, it must nevertheless analyze “the characteristics of the shape arising from the graphic representation from the point of view of the function of the goods concerned” (AG Szpunar Opinion § 88).

The CJEU followed its AG’s Opinion on this point and found that the General Court should have defined the technical function of the actual goods, namely, the three-dimensional puzzle, and it should have taken this into account when assessing the functionality of the essential characteristics of that sign (CJEU § 47). The General Court “interpreted the criteria for assessing Article 7(1)(e)(ii) . . . too narrowly”(CJEU § 51) and should have taken into account the technical function of the goods represented by the sign when examining the functionality of the essential characteristics of that sign (CJEU § 52). Failing to do so would have allowed the trademark owner to broaden the scope of trademark protection to cover any three dimensional puzzles with elements in the shape of a cube (CJEU § 52).

This case confirms, after Pi-Design AG v. Bodum, that the CJEU takes the view that the essential characteristics of a trade mark must not be assessed solely by the competent authority based on visually analyzing the mark as filed, but that the authority must also identify the essential characteristics of a sign, in addition to the graphic representation and any other descriptions filed at the time of the application for registration. This is necessary to protect the public interest underlying Article 7(1)(e)(ii), which is to ensure that economic operators cannot improperly appropriate for themselves a mark which incorporates a technical solution.

The image is courtesy of Flickr user Robin under a CC BY 2.0 license.

This article was first published on the TTLF Newsletter on Transatlantic Antitrust and IPR Developments published by the Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum

From the Gemode site:

From the Gemode site:

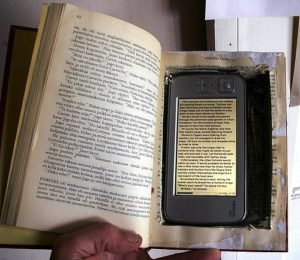

Defendants were charged by a Latvian court for selling unlawfully objects protected by copyright and found guilty. On appeal, the Criminal Law Division of the Riga Regional Court requested a preliminary ruling from the CJEU, asking the Court (1) if the acquirer of a copy of a computer program stored on a non-original medium can resell this copy, in such a case that the original medium of the program has been damaged and the original acquirer has erased his copy or no longer uses it, because in such case the exclusive right of distribution of the right holder has been exhausted, and (2) if the person who bought the used copy in reliance of the exhaustion of the right to distribute can sell this program to a third person.

Defendants were charged by a Latvian court for selling unlawfully objects protected by copyright and found guilty. On appeal, the Criminal Law Division of the Riga Regional Court requested a preliminary ruling from the CJEU, asking the Court (1) if the acquirer of a copy of a computer program stored on a non-original medium can resell this copy, in such a case that the original medium of the program has been damaged and the original acquirer has erased his copy or no longer uses it, because in such case the exclusive right of distribution of the right holder has been exhausted, and (2) if the person who bought the used copy in reliance of the exhaustion of the right to distribute can sell this program to a third person.

Three Copyright Claims Officers

Three Copyright Claims Officers I am writing here only about the two motions and will comment on yesterday’s ruling later on.

I am writing here only about the two motions and will comment on yesterday’s ruling later on.